If I see someone (who) comes in that’s got a diaper on his head and a fan belt wrapped around the diaper on his head, that guy needs to be pulled over,”

– Congressman John Cooksey, a Republican member from Louisiana who sits on the International Relations Subcommittee for the Middle East and South Asia.

Sikhs united at the 2002 Balbir Singh Memorial Annual “Embrace Diversity” Event.

He stood outside his gas station in a seemingly safe suburb of Arizona, a man who had won over the hearts of his neighbors, his customers, the little kids who came in and got free candy and drinks; a man who had given a homeless, out of job American man free pizza day after day, since his arrival a few months ago. He was examining the flowers he had just planted,-four other workers stood near by. A man in a pick up truck pulled in, shot Balbir Singh Sodhi five times at point blank range from the back like a coward, as others watched in horror. The date – 15th September 2001 – four days after the twin towers were destroyed in an act of terrorism master minded by the bearded, turban-clad Osama Bin Laden.

She was all of twenty, and had just returned from Australia after attending an Oral History conference. She was to leave for Punjab, to interview survivors of partition in her grandfather’s hometown, but for Valarie Kaur Brar, images of the crumbling twin towers heralded the rising of something terribly dark and sinister from the ashes. Not much later, a white American man looked menacingly at her through the glass, his eyes full of hatred as she sat alone in her car and asked “Are you Muslim? Are you Muslim?” Racism and ignorance had just made their acquaintance with a girl who thought of herself as a proud American of Sikh heritage.

“DisFunktional Family,” a 2003 comedy concert movie featuring comedian Eddie Griffin, had a scene in which Griffin points to a turbaned elderly Sikh man walking on the street and shouts, “Bin Laden, I knew you was around here!” When the Sikh community protested, the production company Miramax who released the film pooh-poohed their concern by saying reasonable people would not associate Sikhs with Osama bin Ladin, and in any case plenty of people of other faiths wore turbans. Right? Not by a long shot as hate crimes and racial slurs against Sikhs continue to this day.

In July 2004, four Long Island NY men were charged with beating a Sikh priest, Rajinder Singh Khalsa into unconsciousness after ridiculing him for wearing a “dirty curtain” and in September last year Gurcharanjeet Singh Anand, a delivery truck driver, had his home torched in the Bay area. The Sikh Coalition which monitors hate crimes against Sikhs has logged on over 300 hate crimes and bias incidents since Sept 2001, including the vandalism of several Sikh gurudwaras.

Twenty-one-year-old US Army Specialist Uday Singh became the first Indian and Sikh to die in Operation Iraqi Freedom when his convoy was ambushed in Habbaniyah near Baghdad on December 1st 2004, but no one seemingly cared as the Sikhs continued to be targeted and attacked, arrested and abused in the aftermath of the World trade center tragedy.

The community known for valor, patriotism, an enterprising spirit and generosity, has never been too far from bloodshed, and derision. In spite of forming a miniscule percentage of the Indian population, stories of Sikh valor and sacrifice have been written in gold in the annals of India’s freedom struggle. That never-die spirit has made this small community a force to reckon with today in North America and perhaps any place the Sikhs have chosen to make their home.

The first Sikhs came to Canada in 1902. Between 1903 and 1908, over 5000 Punjabis migrated to North America, mostly illiterate and semiliterate laborers from agricultural and/or military backgrounds. The Punjabi immigration to the United States happened because Canadian borders were shut off. The Sikhs who came in, worked as laborers in the lush lands of California and Mexico, many marrying Mexican women and raising mixed families. The Mayor of El Centro, David Singh Dhillon is a third generation Punjabi Mexican American. Others like Valarie’s grandfather waited till they could go back to India and marry a woman from their own community. Later many of them became affluent land owners.

A Sikh entrepreneur, Jagjit Singh, arrived in the U.S. in 1926 and became President of the newly formed India League of American kin. He won over the media and persuaded Congressmen and diplomats to help in the fight for equality and justice, requesting the restoration of citizenship to Indians, denied since 1910. Finally in 1946 Congress passed a bill granting naturalization and immigration quotas for Indians.

It was a decade later that a Sikh farmer by the name of Dalip Singh Saund from an uneducated Sikh family in Punjab, arrived here in 1920 and earned a Ph.D. in Mathematics from Berkeley. Saund went on to become a judge in 1953 and a Congressman in 1956, a feat that went unrepeated until last year when Bobby Jindal won from Louisiana. After 1965, immigrant laws were modified and a lot of Sikhs, who migrated after world war Two, were mostly students, technocrats and businessmen. Their hard work, passion and positive spirit helped them carve a niche in the main stream in all walks of life. From being blue collar laborers, farmers, taxi cab drivers, auto-mechanics, gas station owners, and managers in 7/11 stores, today Sikhs are among the top academicians, professionals and entrepreneurs in the country. Dr Narender Kapany is recognized as the father of fiber optics and is renowned for his invention in the areas of fiber-optics communications, lasers, biomedical instrumentation, solar energy and pollution monitoring. Kanwal Rekhi and Kavelle Bajaj were pioneers in information technology entrepreneurship. Alexei Grewal won the gold medal for the United States in the Mens’ Road Race in the 1984 Olympics and Satwant K Dhamoon is considered among New York’s leading gynecologists.

ASSIMILATION

As things started calming down Sikhs began moving back into the mainstream. Till the late 80s, finding work for a turbaned, bearded Sikh, even if he had the highest academic qualifications, was like finding a needle in a haystack and assimilation was not easy, either for those early immigrants or for their children.

Jeet Bindra

Jeet Bindra arrived in Seattle in 1969 with 8 dollars in his pocket. “It was a very strange feeling,” he recalls, “to be dumped in a land where no one looks like you. You wonder if they have the remotest idea where you are from, and will they treat you nicely?” Bindra did not know a soul and promptly fell sick on arrival. “It was such an isolating feeling. In India even your neighbors showed up bringing food if you were sick, and here I was lying sick and worrying that I couldn’t afford a doctor.” Bindra did what most Indians do- looked up the telephone directory and called a doctor with a Punjabi name.

Bindra worked as a cook, a research assistant, to pay off his loans. “I got questions like what is under the turban, why does your beard stick to your face since I tied it with a thread. It got more difficult to keep my hair when I started to work at Chevron in 1977.”

Bindra was placed at the lowest rung of the ladder and told a couple of years later that even though his work was outstanding, he looked different, talked with an accent, had a turban and facial hair so he would be lucky if he managed to get into even the middle rung. “I was furious.” Bindra decided to fight the system and started taking evening classes to improve his English speaking skills, joined the executive MBA program to hone his business skills and three years later got his first break into the management area Bindra says though the Sikhs are hardworking they tend to try and create a little Punjab wherever they go and are held captive by self imposed bonds of ethnicity. “I have had to shatter several myths-that Sikhs and Indians in general don’t work hard in the corporate culture, they are never on time and they are technocrats and unable to manage people.” Today Bindra is among the top hats at Chevron.

Jagtar Singh

Jagtar Singh moved to the US in 1985 when not yet 10. The transition was tough. Jagtar’s father had to seek manual labor to make ends meet, his mother had to learn to read and write English. “One time someone tried to pull off my turban, another time a girl even cut off some of my hair, and I didn’t know English, so I would get into fights all the time.” Jagtar decided to channel that frustration and aggression by excelling in academics and extra curricular activities. Jagtar says while it was tough being singled out, it allowed him to develop in a way he wouldn’t have, had he not been so challenged to prove his worth. “I came from an affluent family in India and took things for granted. I used to skip school all the time, and I was a very poor student. I remember the time when I was leaving for USA, my teacher commented in Punjabi, “ People like you remain good for nothing wherever they go,” and I thought well may be she is right. In any case we will return and I will just take over the family business.” Working at a gas station while in junior college he says he met the whole gamut of people there-those who were nice and those who told him to go home. Jagtar did very well on the MCAT and was pursued relentlessly by the armed forces, until he told them he was a turbaned Sikh and had to explain what a Sikh was. The calls ended and recruiters made several excuses as to why they could not take him. “One of the people, who told me why I couldn’t be taken, was a woman. I said to her – “You of all the people should know about inequality and discrimination.” Today Jagtar is at Yale medical school, the only Sikh physician, studying anesthesiology. In academics too, says Jagtar he met people who were rude and closed minded. At the hospital, one patient said to him after they spoke – “You speak English good.” ‘You mean I speak English well, don’t you?’ was my response,” says Jagtar laughingly and adds, “No one, however, has refused treatment from me and when you put it all in perspective this is so trivial compared to what the Sikhs have endured in the past.”

Dr. Pashaura Singh had just finished college and started a career in teaching at a Sikh High school in Delhi when he was offered an opportunity to move to Canada in 1980 and perform educational and priestly duties at a beautiful new gurudwara built in Vancouver. Singh arrived with his wife and two kids and found a very welcoming professional community of about 10,000 Sikhs. He recalls that because there were two Sikh doctors in the hospital, most Canadians living there presumed every turbaned Indian was a doctor-a myth he had to constantly shatter. Dr. Singh later moved to Toronto to do his PhD and then to teach at the University of Michigan. He says he realized after moving that unlike Calgary, a vast majority of Sikhs living in Toronto were semi-literate blue collar workers. He saw racial attacks on the gurudwaras when two teenagers were nabbed and forced to do community service at the same gurudwara for 20 Sundays. “They were changed young men after that.”

Maninder Singh

Pashaura Singh’s son Maninder (pictured left) lived in a gurudwara with his parents and had no contact with children who were not Sikhs or from a Punjabi background. “ So when I went to nursery school, no one wore a patka or was even Indian. My first best friend was a Vietnamese girl named Leslie, and we gravitated towards each other because she too looked different from every one else in terms of color and ethnicity.” Later in elementary school Maninder was bullied, his patka squeezed, and called names like turbie. “I would get off at the bus stop weeping.” Maninder’s father went to school and made a slide presentation on Sikh culture.

Being raised in a gurudwara made it easier to embrace everything at face value, says Maninder because every body else did the same thing. It was later that Maninder, started questioning what kind of a Sikh he was not just outside but even within the Sikh community itself. Even the question of whether to be or not be baptized was a huge issue. “Not to smoke or drink or cut my hair was something I had considered to be the norm because it was so in my house and the exclusive Sikh community I had lived in previously, but coming to Toronto changed all that.” Maninder says what made it even more significant was that he saw other Sikhs including some of his own friends, who drank, smoked and had cut their hair, passing judgment because he didn’t.

Maninder went with a friend to teach young Sikhs about Sikh culture in Yuba City and, he found the city to be secluded and isolated. “The knowledge and intimacy of Sikh culture was intense and unpolluted as far as the language, culture and food was concerned, but these people were not exposed to academic engagement or intellectually stimulating environment. As a result they did not research nor understand the philosophy and the spiritual aspect of the religion. I heard things like-if you take your kirpan out you can’t put it back in the sheath till you draw blood.” I had never heard of that. It was almost fundamentalist. There was no understanding of what their religion truly propagated. Then there were the academicians and scholars who felt being academic meant they had the privilege not to practice their religion and cutting their hair was okay. My philosophy was of existentialism”. Maninder says it got harder being pulled in so many different directions. “There were the fundamentalists, the scholars, the secular, and then the non Sikhs and through it all I had to strive to be the Sikh who didn’t drink, smoke or cut his hair-the oddity within the minority. I forced myself to mingle, to become more outgoing, to break cultural barriers out of a need for self preservation.” Maninder says his parents approached racism through assimilation “They would ask my sister and me to correct their accent. Dad armed himself with whatever was needed to fight bigotry-whether through increasing his vocabulary, knowledge or through educating others. Mom learnt more about the social norm. Interestingly it was us helping our parents assimilate and not the other way around! But somewhere along the way we were losing our communication with them, and could no longer see them as people who understood what we were going through.” Maninder found racism to be more subtle in Canada. “It’s a lot easier to confront and deal with it in the US because it’s so vocal and in your face.” Maninder confronted things with humor and as a musician in a school band and later in a very successful fusion band Funkadesi he was able to meet people outside of the box.

Dr. Inderjit Singh came to USA in 1960 and found a mere three Sikhs in New York and the nearest gurudwara 3000 miles away in California. A lady at the subway station wild guessed that he must be from Cuba. When he quipped impishly that he was from Chicago, she said innocently-that’s right, you’ve got to be from somewhere.” He also laughingly adds that he married an American and pulled the legs of his wife’s relatives, most of whom were from a small town in Minnesota and would ask if he had power in India, and did he have a car? “I said we are middle class people so we just have two elephants, one for grocery shopping and one for riding around! To which they asked where do you park your elephant? “

Dr. Singh switched from dentistry to teaching and moved from Oregon to NYU in the 1970s. “I found more acceptance in Oregon than in New York. Sometimes when I was lonely I would go and sit in a diner near a church on a Sunday and after church as people trooped in for lunch, someone’s missionary zeal would be aroused and I would be approached, so that my soul could be saved.” In the process he learnt a lot about Sikhism because he was invited by churches to talk to the people and had to delve deep into his own religion to come up with answers to questions he had never thought about in India.

Dr. Inderpal Singh migrated to east Texas with his family when he was 14. His father found a job in a small college and faced a lot of discrimination. “He was always working in black colleges and knew he was not getting a job in better schools because of the way he looked.” They were the sole Sikh family there. Dr. Singh recalls how he would be shunned by his class mates when he started middle school, because of the way he looked. “I was openly boycotted and discriminated against. Nobody wanted to talk to me.” He would go home and tell his parents and they would ask him to stay strong and focus on his education. For Singh excelling in academics became the antidote for discrimination, he faced in school, as did the weekend trips to the gurudwara where he met other youngsters facing similar issues like he did. College mercifully was a happier experience and he had many opportunities to speak about the Sikh culture. Singh also got involved in the India Association and organized bhangra demonstrations which were very well received. Dr Singh also taught High school and would welcome curious questions from the students. Eventually he went back to school to study medicine and is a physician.

Ujjal Singh Dosanjh

Ujjal Singh Dosanjh grew up a shy kid in a very secular village and says he was never conscious of his faith because of the strong interpersonal relationships. “ Its when you come abroad that your religious background becomes more accentuated because there is nothing else to anchor you.” Dosanjh decided to study abroad and got admission in a college in England. He left as a teenager, worked during the day to make money and attended night school. He says while he was really not aware of the complexities and consequences of the British rule in India he always felt at odds with the society in England. A chance encounter with people at the Canadian High Commission opened the passage to Canada. Dosanjh landed in British Columbia, worked during the day and went to law school at night. He went onto become the first Indian and Sikh Prime Minister of the province. Today he has come out of semi retirement to hold the key post of Health Minister in the Canadian government.

T Sher. Singh grew up in Patna and says he was usually the only Sikh and also the youngest in his class and would be picked upon. “ I responded by becoming quite a fighter. Being attacked by bullies and fighting back became a daily occurrence and I was more a minority growing up in India than I have ever felt or been in Canada,” says Singh who has lived in Canada since 1971. Singh says when he arrived here, he stood on a quiet night looking outside the hotel window, at the shimmering lights as his siblings slept and realized he belonged here. The transition was easy because his own family as well as his extended family had moved together.

T. Sher Singh

Singh says there were very few Sikhs, and the community did not have any infrastructure or an organization one could turn to. Singh enjoyed learning about other cultures and encouraged questions about his own. “Answering those questions taught me a lot about my own religion and my own self and who I was. It wasn’t easy. Answers like I have kept my hair because the gurus said so, may be acceptable in India but weren’t here. It was after coming here that I truly started becoming proud of being a Sikh as I discovered so much about my background and heritage.” Singh says he had a lot of difficulty finding work even when he was intellectually ahead of his peers. He was underutilized, underpaid in the corporate world and had a lot of difficulty moving up. In 1977 Singh was interviewed by the second largest stockbroker company, offered a huge salary and asked to shave off his beard and cut his hair in return. Singh walked away, did odd jobs delivering papers, as a security guard, a courier and didn’t regret his decision even once. In spite of that Singh feels that it is easier being a Sikh in Canada than the US. “The US is very fundamentalist and Christian despite its protestations that it separates religion from state and I don’t say this as a criticism but as I perceive it. So there is a lot of pressure when you practice any other faith.” Singh is a writer and speaker par excellence and ranks amongst the toughest attorneys in the country today.

IRAN AND INDIRA

During the Iran hostage crisis, Sikhs were mistaken for Iranians because of their turbans and faced racial profiling. The assassination of Indira Gandhi in 1984, the attack on the Golden Temple, and subsequent violence against Sikhs resulted in a deep disillusionment with the Indian Government. It was the turning point for many Sikhs who left India in large numbers. The demand for a separate state by a small segment of hardliners, cast a dark shadow of suspicion over the peace loving larger Sikh population.

Balbir Sodhi’s brother Rana says his family owned lands and also ran a business back home in Punjab. They were caught in the midst of the turmoil. “If you didn’t agree with those Sikhs who wanted to create a separate state, they came after you and on the other hand our businesses were closed because the government would target the Sikhs and impose indefinite curfews. So how does one survive?” Sodhi’s parents felt their children would be safe outside India-so five of the Sodhi brothers, arrived one by one to the USA starting in the late 1980s. The brothers including Balbir, worked in the fields and 7/11, even drove taxis, before they got into the restaurant and gas station business, and moved to Arizona. Only one brother Sukhpal stayed on in San Francisco, driving a cab.

Raj Nijjar

Raj Nijjar, an engineer and a popular singer based in Washington DC recalls that on his college campus in the 80s people knew each other, so there was no discrimination. “Outside, on the roads and especially at the CRPF “nakas”, however, a flowing beard and turban was not treated well. Despite that and the regular news about Sikh youth being killed in (fake) encounters with police, I did not feel more unsafe than others in Punjab. Immediately after Indira Gandhi was killed, there were seemingly planned riots against Sikhs. “That’s when I started seriously thinking and planning to get out of India.” Nijjar came to the Virginia/DC area and found a good number of Sikhs there. He says the Sikhs were hurt and angry that all the suspects identified in independent reports were not even questioned. “What struck me most was how openly everybody spoke their mind and how different it was from back home, “ says Nijjar, “Majority of the average Americans were either ignorant of the situation with the Sikhs or did not care much. Others perceived Sikhs negatively due to the government orchestrated news coming from India. I remember explaining to many my personal experiences and other events and perspectives they never got exposed to. I had always known the power of the media but it was only then that I realized how powerful it was.”

Dr. Harinderjit Singh a prominent eye specialist, based in Augusta, Georgia, remembers an incident in 1983 even before the assassination happened. He had gone to India with his wife and daughter and was told by a cab driver’s assistant “Khalistan banega toh aapko dekh lenge(if Khalistan is created you will pay for it). “There was hype by the government and the media that had warped the minds of people there, and changed the way they perceived us.”

He was in the Masters program, studying psychology when Surinder Lalli headed a peaceful march against atrocities in Punjab in the eighties. He was put in jail, his brother disappeared. Twenty years later his brother’s body has not been found and the mystery remains unsolved. “Initially Sant Bhindranwale simply wrote a letter which was published in the papers all over, and all he asked was that the people who murdered the Sikhs should be punished or the Sikhs will have to take matters into their own hands. I knew Sant Bhindranwale. He was a very religious man, a little stubborn but he never wanted to hurt any one,” says Lalli. Lalli adds that he believes Bhindranwale was used as a pawn by the government, leading to the cooling off of relations between Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs. Lalli moved to USA in 1991 because his parents feared for his safety and is a successful business entrepreneur in Atlanta today.

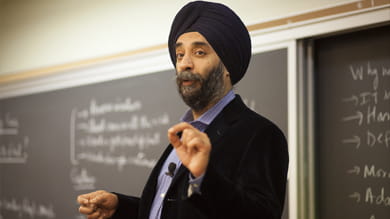

Dr. Mohanbir Sawhney

Dr. Mohanbir Sawhney who came to the US in the 1990s to do his PhD at Wharton Business school and currently teaches at the Kellog School of management, says he was in Delhi when the event happened. “ When you are sitting thousand of miles away you tend to have more of a black and white opinion of what happened, but as I saw the fires burning in Delhi in the aftermath, it was very clear to all of us that there was government involvement. My take on that was that Mrs. Gandhi was the master in the art of divisive politics-she played with fire and got burnt. Bhindranwale was the creation of Indira Gandhi and Giani Zail Singh. Mrs. Gandhi encouraged the fundamentalist Sikhs, divided the akalis and then couldn’t control things. My father has lived through partition and we never believed something like this could happen. Some of my relatives left in the aftermath” Sawhney says that he felt more discriminated against in India than in the US.

“In order to develop discrimination one needs to have a minimal level of awareness of the popular stereotype. Sikhs were such a minority and such an oddity in this country that people did not know enough to stereotype and discriminate, until September 11 happened, but in India there is a well formed stereotype and hence a clear discrimination. While recognizing the challenges my children may face here I can say growing up in India as a Sikh was pretty tough as well, especially in the south.” Dr. Sawhney also says that he feels a sense of shame when he says that Indians who live in the US are greater racists than most people.” We have a very strong sense of cultural and racial identity. Every one is a Hindu, Punjabi, Malaylaee, and Gujarati first and then an Indian, and they bring it here as well”

Dr. Harinderjit Singh

Dr. Harinderjit Singh had similar experiences of discrimination in India all the way through college and then moved first to Canada to study medicine and then to the US thereafter. While several Sikhs were asked to cut their hair off in order to move up the rung, Dr. Singh had a contrary experience. “I had recommended a good fried of mine who was a clean shaven Sikh for residency. He was interviewed and rejected. The reason given-if he could not stay true to his faith and cut his hair-how can he be true to his patients.” Singh says while he never faced any discrimination in Canada and the US from the mainstream, but strangely in Philadelphia, an Indian who interviewed him in 1979 was openly discriminatory. “I guess I realized there are good people and good parts of the country to live where you will find acceptance and not so good people and not so good parts you need to avoid.”

Raman Singh an engineer who is also an entrepreneur in Michigan and raising two sons says for her 1984 was a very decisive event. “I was 18 and the attack on the golden temple was really the defining moment for me and for many Sikhs. I couldn’t understand all this talk about Sikhs in India and Sikhs outside of India. I will always be an Indian Sikh by virtue of my ethnicity and heritage-and what am I supposed to try and choose? To be a Sikh and not Indian, or to be an Indian but not a Sikh? It was a very emotionally trying year for me. I wasn’t old or mature enough to realize these were all political games, but it did galvanize my Sikh instincts. The intense hatred I felt that year made me even more determined to raise my kids as American Sikhs. They have an Indian heritage but for me it’s more important that they be in touch with their Sikh roots.”

Dr. Pashaura Singh

Dr. Pashaura Singh remembers that while the Sikhs were shocked at the assassination they also held a protest march condemning the atrocities against the Sikhs, where Dr Singh spoke. He was black listed immediately and denied visa to visit India in 1989. “Before the assassination it was a matter of pride for us to be Sikhs, but after 1984, we found ourselves always being defensive, always giving explanations to anyone who would be willing to hear us out or get to know our community better.” Dr Singh says majority of the Sikhs were lumped in one slot of martial gun toting fanatics, a perception, encouraged by the Government of India. Since the US government received all its information from Indian government sources, it became prejudiced as well.

Dr. Rajwant Singh, a dentist who lives in Washington D.C. and heads the Sikh Council On Education and Religion (SCORE) said a memorial service was organized for Mrs. Gandhi but hardly any leader from mainstream America attended the services, because of the misinformation floating around. “It was at that point I decided we have to educate the masses and we have done so through this organization. In Washington, we started interfaith meetings, feeding the homeless, going with other ethnic groups and attending meetings at the Capitol Hill and today any time anything happens in Washington DC we are the first of the communities invited.”

Inder Singh (pictured left) who is based in Los Angeles and was President of FIA (Federation of Indian Associations) at that time, says there was a flip side to it all. Singh who condemned the assassination in interviews with NBC and CBS reiterating that the Sikhs were a patriotic and peace loving race started getting threatening calls from his own community. “Who are you to represent the Sikh religion? they asked said Singh, “How come you say Sikhs are peaceful people-don’t you know that Sikhs have always got everything by the edge of their swords?” Singh says he responded by telling them Guru Nanak Dev and Guru Gobind Singh were messiahs of peace, who said only when there is no alternative must you pick up the sword. In response people fired at his windows, breaking them, and he received threatening phone calls but no one had the guts to actually come forward and hurt him.

BLACK TUESDAY 2001

September 11 showed very clearly that mainstream America cannot differentiate between Bin Laden’s turban and the Sikh one. Even when they didn’t wear a turban the last name Singh was enough to set the alarm bells ringing. Surinder Singh, a businessman based in Atlanta and the grandson of the famous Ghadar party leader Bhai Bhagwan Singh Giani, recalls how once when he was leaving for India the Air France crew would not let him change seats because his last name was Singh, even though he didn’t have a turban on. “I had cut my hair, but kept my beard after the Iran hostage situation when I was heckled every where. This time the Air France crew was so frightened and paranoid, they wouldn’t let me even get up from my seat.”

Maninder recalls going to a memorial service in front of the city hall in Chicago post-September 11. He wore a red, white and blue turban and a woman came up to him and said she forgave him and his people who were part of the Islamic culture. “She was appreciating the fact that as a Muslim I had come to show support. It really wasn’t the time and place for me to start explaining to her that I was a Sikh,” says Maninder who just gave her a hug and let it go at that. Another time at a movie theater a black man looked at him and said to his buddies – “there is a suicide bomber sitting in the third row.” Maninder found it strange to see a member of a community that has faced racism throughout make a wisecrack like that.

Dr. Inderjit Singh recalls walking down a street in New York 2-3 days after 9/11. He had traveled the same route and saw the same people every day. “But now they looked at me and then looked away. There was a sudden coldness, a sudden pain in their eyes. Suddenly they didn’t know who I really was.” Singh got into a conversation with a man who said to him “When you people came here why didn’t you leave your religion at home?” Dr. Singh responded, “My people have been here a mere 100 years. When your people came here from where ever it was, did they leave their religion behind? We are all from somewhere. The immigrant society, the immigrant culture is really our strength. This society is not a melting pot but a mosaic where every little piece has its own unique place and the whole is greater than the sum of those parts.” The man appreciated that and had a cup of coffee with him.

Rana and Harjit Sodhi

Rana Sodhi is still in a state of disbelief about the aftermath of September 11. Until then, he says his brothers and he never felt unsafe or discriminated against. “I could go anywhere in the country without fear. I too drove a cab for a little while. It is considered a high risk job, but we never felt we had any cause for concern.” Rana recalls that on the morning of September 11, he was still at home when both his brothers Balbir and Harjeet called him and asked him not to go to work because something had happened in New York and they were showing something about turbans. “I told them, nothing is going to happen here. They were worried because I worked in the downtown area which was considered unsafe as compared to the suburbs Balbir had his gas station at”. Rana went to work, and realized things had indeed changed very rapidly. “People were showing me the finger, a loyal customer called in asking me to be careful..things were heating up. We went shopping to get things for our stores and could see people acting differently even the ones who had been our frequent customers because we had our turbans on.” Balbir decided the Sikhs needed to act quickly and after talking to their gurudwara priest started working along with his brothers towards meeting with the media and government officials to educate them as to who the Sikhs were. Four days later he was shot dead. The killer Frank Roque, an engineer, claimed it was an act of patriotism then pleaded insanity. “ It was proved by one of his colleagues that it was a premeditated attack because he had told co workers openly he was going to kill those rag head people and their children,” says Rana. Even after Roque, who was given the death penalty found out the truth, the Sodhi family (pictured below at a press conference the day after Balbir’s shooting) has yet to receive an apology from him or his family.

Ten months after Balbir Sodhi was shot, his brother Sukhpal was gunned down in San Francisco in what was obviously a racially motivated attack, though the police wanted to call it a random shooting. “All his belongings, along with $ 300 in cash in his pockets were found intact. How can we believe it was a random act of violence?” asks Rana. For the Sodhis this dual tragedy has shaken them but what helped the family move towards healing was the outpouring of love that engulfed them. Four thousand people turned up at the funeral. “It is that love that has given us strength.” Says Rana. Balbir Sodhi’s three children have since then moved to Arizona as well.

Valarie Kaur

For Valarie Kaur, the September 11 tragedy and the violence against the Sikhs in its aftermath came as a rude awakening. “My email was flooded by stories of Sikhs who were being attacked, abused and shunned and it was then that I realized the magnitude of what was happening to the Sikhs. I knew Balbir Sodhi’s family through a close friend and when he was killed, it made me catatonic.” It took the Bush administration more than a week to acknowledge that the Sikhs were also Americans and Valarie says she began to recall all the history projects she had done in school to acquaint her class mates about partition, about 1984, events that had gone undocumented in history books. She began wondering if the aftermath of September 11 and the atrocities on her community would also face the same fate. “Growing up in my small home town of Clovis, where every one knew each other, I was never conscious of my color, and yet as I ploughed through the country I realized I’m much more a part of my community than I had earlier realized.”

Valarie initially wanted to shy away from her Sikh identity. Then Guru Nanak’s words echoed in her ears “To realize yourself you must act,” and at that moment she decided to do just that. Along with her cousin brother Amandeep, for four months she traveled all over the country videotaping and recording the experiences of Sikh Americans. Once she started visiting the Sikh gurudwaras and homes of people, they began sharing horrific tales of the backlash they had faced. She learnt about the Sikh man who reached out to help when the twin towers came down and then had to run for his life as people turned on him accusing him of terrorism. She met a woman who is Sikh but has short hair. She was stabbed because of her color and told, “This is what you get for what your people have done to us.” It hit close to home when people started yelling at her turbaned brother and her at a gas station in Washington DC. They were told by a man walking by to go back home.

Valarie recalled talking to children at a youth seminar at a gurudwara in Atlanta and asking them the meaning of “Sewa”. The response -to help those on the outside. When Kaur asked who were the outsiders she received responses ranging from international kids, kids with disabilities, those who don’t have friends, and then a little Sikh boy raised his hand and said “ourselves”. Kaur was stunned into silence. Armed with a lot of footage, Valarie came back to Stanford and converted her journey into a thesis which combined the narrative of the people with her own analysis of the causes, impact and long term challenges it posed for America and the community. The thesis won her the gold medal.

Today Valarie is at Harvard studying the effect of violence on religion. She is also converting the documented footage into a full length documentary film and trying to raise funds to make sure it is completed the way she has envisioned it. Her thesis is being rewritten as a book for the mainstream. “1984 and the partition-.all those stories were history lessons for me,” says Valarie and adds that the war in Iraq, the famine though happening in her time were a distant reality that she couldn’t connect with. The tragedy of September 11 changed all that. “I became a part of the dark history of terror, violence and hatred that was being created, and it has become a mission to speak up. The Sikhs must stand up and fight for themselves, because now the difference between speaking up and staying silent becomes the difference between life and death.” Valarie has since then spoken at conferences, film festivals, academic institutions and gurudwaras. A course on Sikhism that she co created is now a model being adopted across the nation by many universities.

Inder Singh says that what is gratifying is that September 11 gave the Sikh community exposure and galvanized the whole community into action. Vigils were held in every city and politicians, law enforcement officers, and members of other ethnic groups along with the media were invited to learn more about the community. Jeet Bindra recalls that SALT(South Asian Leaders of Tomorrow) did a survey on hate crimes and found there had been 600 odd hate crimes in the first 30 days and victims included Sikhs and Muslims from India, Pakistan, and Middle east. “We immediately prepared and distributed hate crime videos to all non profit organizations and stressed on education and saw a significant and positive shift in understanding.” Law enforcement and the DA’s office hired Sikhs, and Sikhs were also brought into advisory committees.

Dr. Rajwant Singh says the Clinton administration was the first to invite the Sikhs formally to the White house. “That created a lot of recognition and credibility for the community and began the initial recognition and dialogue process. Mainstream America took note as well.” Singh adds that the Bush administration has gone out of its way to show their support for the Sikhs especially after 9/11. Another very positive development after 9/11 is the very active leadership role second generation Sikhs have started playing in schools, colleges and gurudwaras to create awareness about the Sikhs. “The younger generation of Sikhs has always perceived themselves as Americans and not Indians. For them to see the violence and the discrimination against their community in a country they call home has been a shocking experience. For the first time they felt like they didn’t belong. My generation had the same feeling after Indira Gandhi’s assassination. This has galvanized the entire community of young Sikhs into action”.

THE GREAT GURUDWARA DIVIDE

The Sikh Gurudwaras (religious temples) abroad have been a haven for the community and a place to stay for transit passengers of all ethnic backgrounds since the early 1900s. Originally the gurudwaras were meant to be spiritual centers for prayer and socializing, says Dr. Pashaura Singh, and also to discuss political issues worldwide in a secular way. They were expected to run Sunday schools to teach the younger generation cultural and religious values, along with Punjabi, music and language and to liaison between government authorities and the Sikhs. Somewhere along the way the role of the gurudwara became a bone of contention among the Sikhs, resulting in ego clashes, mayhem and even murder. The religion whose tenets embrace universal love and brotherhood, equality of gender and religion has had to bend its knees before human ego and issues of control.

Jeet Bindra says he is religious but he prays at home. “I hate going to the gurudwaras which are no longer the place of love, worship and acceptance or where we should be educating our children and general public about our culture and heritage.” Bindra recalls the power struggle within the gurudwara system in California which let to the shooting and killing of a person who didn’t agree with others. “It’s a shameful thing. People who don’t know our background will presume that we are a violent lot who will kill for the smallest digression. I also hate it when I see gurudwaras being used for political purposes or to further personal interests”

Inder Singh says there are hardly any gurudwaras where they perform services in English for the younger generation which is most fluent in that language. The priests at the gurudwaras struggle with whether they should worry about the younger generation or stick to catering to the older congregation most of whom migrated from India and know Punjabi and Gurmukhi and finance the running of the gurudwara.

His wife Deepi Singh says the bible has been translated into so many languages. Why can’t we translate Gurbani into English? “I teach our religion to my grandkids but how many children have the privilege of living close to their grandparents? If you offer suggestions you are rudely told by the management we don’t want advice from outsiders. How am I an outsider? I am a Sikh woman who has been an active participant in the local community activities.”

Dr. Inderjit Singh agrees “Today it’s all a mess. Or gurudwaras these days raise funds for dubious causes, their book keeping is horrendous, they cheat during their elections and do not think beyond the four walls of the community.” He adds that the elders built the gurudwaras initially to capture the sights and sounds and smells of home, but the sights sounds and smells are not the same for the youngsters who are born and brought up here. Dr Singh finally told the youth they were going to inherit these institutions and it is up to them to bring the change. As a result the youngsters have started teaching English as a second language, they held blood drives and commemorated the bloodshed of 1984.

Dr. Inderpal Singh

Dr. Inderpal Singh, a family physician based in Atlanta says, growing up in a small town in Texas when he moved from India in his teens, was tough. He was shunned by his peers, his father couldn’t find a teaching job except in black colleges, and one of the key things that helped him fight the feelings of alienation and loneliness, were his weekend trips to a gurudwara where he met other Sikh youth and knew he was not alone. That is why, he along with other fellow Sikhs is making sure that the community in Atlanta focuses towards making gurudwaras more accessible.

“We are creating programs for Sikh children so they can understand and appreciate their cultural heritage. We have a little survey to help young Sikhs on how they can better equip themselves with issues of discrimination.” Dr Singh adds that they are also helping groom the youth so they are well equipped to represent their community in the future. In Atlanta they have the SEWA project, where the whole service, and langar( community luncheon) has to be done by the youth and they project the shabad(religious hymns) on a big screen in Punjabi and English “While being a Sikh starts at home the roots have to be nurtured for it to evolve well.”

SIKH WOMEN

Perhaps no other religion stresses more on the equality of sexes than Sikhism, with Sikh women even having led armies in to battles, but the rights of women seem equal only in theory according to Dr I.J. Singh. So what does it mean to be a Sikh woman in mainstream America and within the Sikh community itself? Perhaps their challenges are similar to women of other ethnic communities in most ways but many Sikh women feel being an ethnic minority and a Sikh woman on top of that can be a double whammy.

Raman Singh came to this country as an infant and says as a child she felt very isolated as her parents juggled several hats-trying to raise children, and establish themselves financially and professionally. “I remember always being torn between two cultures, sometimes as an Indian and at others as a Sikh, wishing I could just celebrate Christmas like every one else and get on with life.” Raman also feels the perception that it is easier to be a Sikh girl than a Sikh boy was incorrect. “Beyond the turban, there is still a huge divide between the mainstream culture and mine. Also girls place a different pressure on themselves than boys do, and there is always racial discrimination, taunting and issues related to dating. My parents didn’t know of the problems I faced in trying to assimilate and still remain Sikh. I probably did things I haven’t told them about but at the end of the day I always knew I was Sikh and would marry one.”

Manpreet Kaur

Dr. Pashaura Singh’s daughter Manpreet Kaur studying medicine in Ohio, said for her being uprooted from India was traumatic. “We were the only “colored” people in school.” When she moved to Toronto as a teenager, she was asked during gym why she didn’t shave her legs, that it was unhygienic. “It was not even about my long hair or skin color-I was often mocked by the boys and had to stand up for myself. My brother stood out because he wore a turban, but growing up was no less traumatic for me, so I could relate easily to the sense of alienation he felt.”

Manpreet says such experiences made her more compassionate and she got involved in minority advocacy groups as a result but she felt a deep sense of alienation when she saw Sikh women being attacked or picked on because they wore a turban, or when someone told her to go back to where she came from thinking she was Muslim. Preeti says for her there weren’t any women role models other than her mother who managed to juggle work and a home fairly successfully. “There is a Sikh Sisters network that has attempted to create opportunities for young Sikh professionals to support each other with retreats which are very enriching but the network isn’t nationwide and can be financially and geographically limiting for many women. There are chat groups but limited to friends.” For social services the Sikh women still rely on mainstream help resources in cities, though on a national level there are activities that help spiritual and social growth among Sikh women.

Gagandeep Kaur

Gagandeep Kaur grew up in New York and is currently in California. She started a small literary magazine as a teenager called Sikh Generations. Among other things, Gagandeep had written a feminist piece on domestic violence called “Her Silent Cry.” “One out of every five women in the community has been molested by a friend or family member before they reach 18 years of age.” Her work received tremendous appreciation, and while they were talking mostly about Sikhs and Sikh issues in the US they started receiving subscriptions from France, New Zealand and Australia.

Today Gagandeep is involved in many non profit organizations and has been the first woman to head the national advocacy organization SALDEF,( formerly known as Sikh Media Watch and Task Force). It didn’t even occur to her that she was a woman heading the organization and that it was a big deal until she realized all her counterparts in various other organizations were men. Gagandeep says USA remains a male dominated society even more so than India which had a woman Prime Minister more than 3 decades ago. “ Here I remain a colored woman living in a male dominated society and world; a minority within my own ethnicity.”

Deepi Singh, who is married to Inder Singh, says that Sikh women in general are very well educated, liberal and open minded and she is a member of one such women’s group. When they are together they discuss everything but when the men are around they keep their mouths shut. “The men want to hold the fort and who wants to argue with them!”

Tia Sawhney, an American married to Dr. Mohanbir Sawhney, says what bothers her is the way most Sikh women come to this country-through marriage and are stuck in apartments in the suburbs, without public transportation waiting for the husbands to come home and take them grocery shopping. Their degrees mean nothing in an American job market and they have nowhere to turn to even when there is abuse. “No wonder their voices aren’t heard much in the gurudwaras. The young girls growing up in the country are doing very well but the language barrier keeps them away from the gurudwara as well”.

Dr. Varinder Singh

Dr. Varinder Singh, a physician based in Atlanta feels that Sikh families are more liberal than other South Asian families and she sees some women who are very strong and play a key role in the family as homemakers as well as professionals. Compared to other ethnic minorities a lot of Sikh women are coming forward and taking on key projects. The clergy remains a male domain because she doesn’t see too many women wanting to play a key role in the gurudwaras. It is up to the women to stand up for themselves.

Dr. Inderjit Singh recalls that once New York Times decided to cover the celebrations of a Sikh festival and he asked an elderly lady to lead the Congregation during the religious services. She did but he faced tremendous hostility and backlash from his male colleagues for initiating that. He does see things changing for the better now as the younger generation grows up. “Younger women are forming associations, getting into management positions and saying we are supposed to be your equals-well prove it.”

T. Sher Singh agrees and says where ever he sees women involved, things have gone very well and that women should comprise of 50 percent of the gurudwara management committees. Singh says more and more Sikh women are going for higher education especially in Canada unlike a lot of the Sikh men. “When they choose to step forward, Sikh women excel wherever they go, since there is no theological reason for them not to. The challenge soon will be whether Sikh men can measure up to their standards of excellence, and stay at par.”

Shabad Kaur Khalsa and Shiva Singh Khalsa

THE OUTSIDERS LOOKING IN

Shiva Singh Khalsa (pictured left with his family) is an American Sikh Priest of Greek origin. His life changed when he met his guru Harbhajan Singh Yogi 36 years ago and embraced Sikhism along with his wife and sister. Khalsa says in his eyes, a true Sikh is one who meditates on God, serves humanity, lives honestly and gives part of his earning to the needy. He observes that Sikhs have struggled both in India and the West to establish their identity. On top of that to have American Sikhs like him in their midst was tough. “But now 30 years down the road immigrant Sikhs respect my American counterparts and me. When 9/11 happened, we stood next to the Punjabi community to represent the Sikhs.” Khalsa says he is happy to see so many Sikh women wearing the turban. Many gurudwaras where American Sikhs are involved, have started offering English translations during the religious discourses, after they are read out in Punjabi and Gurmukhi. “Earlier we had to translate everything in English for ourselves.” Khalsa says they have been running a school in India for the past.20 years and all the American Sikh kids who have grown up in Punjab speak fluent Punjabi. “ Some time ago, back in Boston, it was cute to see one of the kids who had come back from India getting ready to play cricket with the other kids”.

According to Khalsa Chicago has what may be one of the first Sikh gurudwara co-founded by Western and Punjabi Sikhs. Khalsa adds that today he can go to any gurudwara in the Midwest and perform services. “I have presided over weddings and funerals. I am also a Sikh minister and treated with great respect.”

Khalsa and the Sikh community in Chicago have been very involved with law enforcement, meeting the FBI and INS regularly since 9/11 to discuss how they can help solve some of the problems between law enforcement, the Muslim and the Sikh communities. Such initiatives have been happening all over the country. “We came out with a training video for the police force which talks about who the Sikhs, Muslims and orthodox Jews were. We have also had a good relationship with major newspapers who have written powerful articles. We conducted several high profile community events around the city of Chicago about Sikh religion and tradition and who the Sikhs are to educate people in the mainstream.”

Khalsa experienced similar discrimination as other fellow Sikhs had because of his appearance even before September 11. He too responded with humor and by conversing with people. “I would pretend to ask for directions and as they gave me directions some of them would say-hey what’s with the turban? I would explain and would go from being a symbol of something they didn’t understand to a human being within minutes”.

Khalsa finds that the Sikh community is struggling with the challenge of finding a happy middle ground between the values Sikh immigrants brought with them from their homeland and the values of American culture. “ Its very challenging for young Sikhs born here to integrate their own expectations with those of their families. I see some young people who identify very strongly with Sikhi and Khalsa and then there are others who are very much disconnected.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.